Equity and Accessibility:

The Foundations for Good Online Course Design

In Module 2, you will:

- Learn about Universal Design for Learning (UDL) as an evidence-informed framework for thinking about making your online courses accessible to the learners in your class

- Learn how to use UDL recommendations to design online learning environments and activities that offer multiple means of engagement, multiple means of representation, and multiple means of action and expression

- Learn about digital tools that teachers can use to design learning activities and courses in alignment with UDL recommendations

- Reflect on ways to design accessible, inclusive learning environments for learners that are informed by social justice-oriented methods

- Practice making a list of ways to design for inclusion and accessibility online

Estimated Completion Times

Estimated Reading Time: 1 Hour

Estimated Reflection Time: 10 Minutes

Estimated Practice Time: 15 Minutes

Table of Contents for Module 2

- Universal Design for Online Course Environments: Introduction

- Using The Principles of UDL to Design Online Courses: Practical Tips

2.1 Think Big

If designing for meaningful relationship-building in our online courses is our first consideration, the design of equitable, accessible learning environments is a parallel priority. These are not separate concerns. All learning is social (Vygotsky, 1978) and shaped by culture and context (Brown, Collins & Duguid, 1989; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, 2018). Online, the context is…well…the Internet. Learning online is situated in a socio-technical network and all of the connections in the network reflect human interests, cultures, systems and structures. It is important to keep this in mind because our work, as online teachers, is to harness the power of this network in ways that benefit all of our students.

Often, school boards (and universities) ask us to use Learning Management Systems (LMSs) such as Brightspace, Google Classroom, Hapara, Moodle, Schoology, or BlackBoard to create online classrooms for our students. These Learning Management platforms are digital technologies, created to offer teachers a range of design options for their online or hybrid course materials. Commonly, they allow teachers to create “modules” that display information according to an organizational structure that is coded into the platform. Information can be multimodal — meaning that it might be text-based, but it also might be presented in videos, in infographics, in audio files such as podcasts, and in combinations of these. When used well, educators can create online courses that are logically structured, and easy to navigate for learners. They are far from ideal, however. Like any tool (think hammer, vice-grips, pencil sharpener, hockey stick, the golf putter) they are only effective when used by humans who know how to make the most of their technical affordances. Even with the best-designed hammer in the world, I am still quite likely to hit my finger as I try to hammer a nail — a master carpenter, on the other hand (pun intended LOL) might miss the mark once or twice a week…but most of the time, they* (use of gender neutral pronouns also intended) hammer nails efficiently, without injury. With learning management systems, teachers are the metaphorical master carpenters. As a teacher candidate, you must learn to leverage your professional expertise so that the LMS you are asked to use becomes just another teaching context where you leverage all of your skills and knowledges about learning, learners and good teaching to create learning activities that work for your students.

As we saw in Module 1 with the screenshot of my daughter’s Gmail Inbox, learning management systems have design flaws that can impact learners’ ability to understand, or to engage with the materials provided. As teachers, when we are aware of what the technologies do and do not do, we can make intentional choices about what to include and what not to include in our online courses. I have a feeling that my daughter’s teachers really did not understand that every time they made an update, their students were getting notifications. But without this knowledge, the unintended consequence was pretty significant.

It is therefore very important for teachers to learn about the Learning Management System and how it communicates with students, how information is displayed, and how students navigate the environment before they create their online courses.

Module 3 will prepare you with a range of important organizational and technical tips about LMSs. In Module 2, however, we focus on the design thinking that needs to happen even before you log in to your LMS to create your first lesson.

Universal Design for Learning in Online Course Environments : An Introduction

It is a pretty common educational aphorism that “everyone learns differently”. You have likely heard this. And maybe you have even uttered this phrase yourself. But as with any “simple truth” there is always so much more to the story. As professional educators, it is important for you to know how and why this statement is both true and not true.

Let’s start with differences.

Certainly, each of us has a unique set of life experiences that form the foundations for how we make meaning from our worlds. Where we grew up, who our friends were, the schools we attended, the families, the religious communities, the land and the built environment around us, the language(s) and cultures into which we were born — all of these things (and so many more!) give us points of reference for making sense of information, and of what we observe, what we feel, and do.

Some of us do have unique brain physiology that means we process the world a little bit differently than others. Some of us have experienced traumas that mean our limbic (emotional processing) systems are very active, and we may therefore interpret experiences through a heightened feeling of stress. Some of us have sensory differences that affect the amount of information we bring into our brains, the types of sensory information that we can process, or that affect how intensely sensory information is interpreted. Some people are blind and others are deaf. Some people cannot smell. Some people (people on the autism spectrum, for example) have heightened senses, or can feel overwhelmed by too much sensory information (e.g., sounds, smells, lights).

Developmentally, our students are progressing through times of incredible change. During adolescence, for example, the prefrontal cortex of the brain is undergoing significant restructuring which means that the pathways that control executive functions (e.g., working memory, the ability to switch between activities, the ability to plan, the ability to critically analyse or anticipate cause-effect relationships) are not yet fully developed.

In these ways, humans do differ. Insofar as our lived experiences and our neurophysiological differences influence the meanings we construct from our learning activities then yes, we can say that “everyone learns differently”.

How are we all the same?

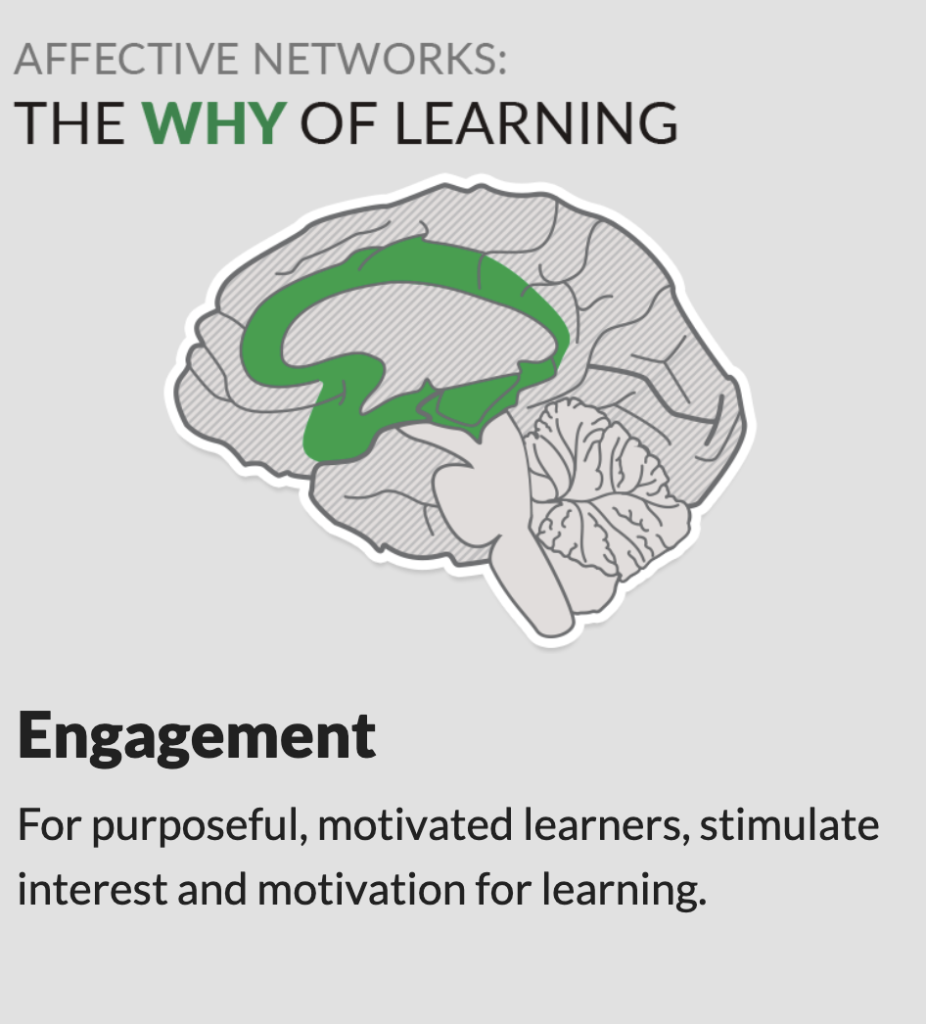

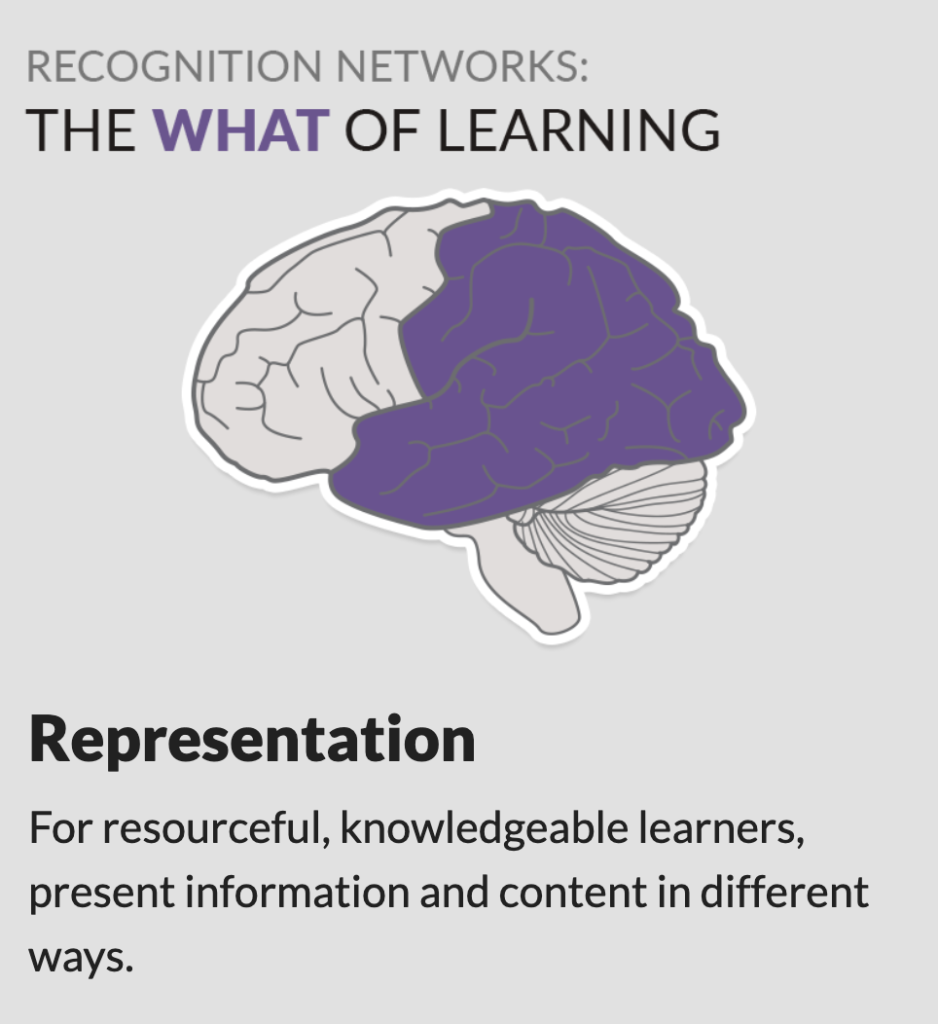

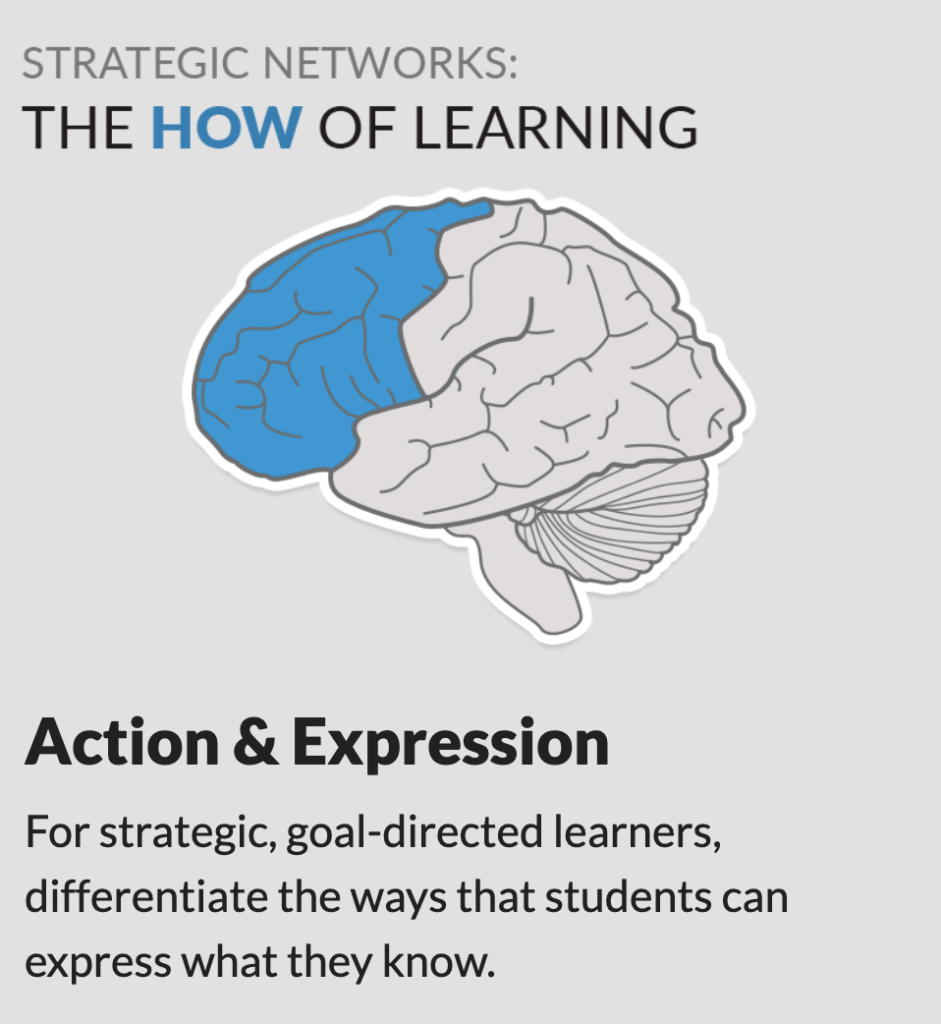

However (and this is really important) most people — even those with uniquely configured brains — have the same basic apparatus for meaning making. Research undergirding the theory of Universal Design for Learning suggests that we are all much more similar than we are different. We have bodies and sensory systems that bring information into our brains, and our brains process information through three main neural networks. As you can see in the image below, human brains have affective networks, perceptual or recognition networks, and strategic networks.

The theory of UDL suggests that when learning activities and environments provide multiple means of engagement, representation, action and expression, EVERY learner will benefit.

What does this mean for online course design, then?

Well, it means that if you design for the ways that we are all the SAME, then most learners will benefit from the design of your online course, most of the time. The principles of UDL are especially important for students who absolutely need multiple ways to engage with course material and to show what they have understood — but the really cool thing about this approach, is that we often find that “neurotypical” kids benefit a great deal as well. UDL is essential for some, and beneficial to all.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Curb_cut_for_wheelchair_ramp_(DSC_3616).jpg

A commonly used metaphor is the sidewalk curb cut. People who use wheelchairs to navigate the urban environment absolutely need curb cuts to safely get up onto the sidewalk but many other people benefit from this sidewalk design feature as well. These include parents pushing baby strollers, older people who use ambulatory supports like walkers or canes, people who might lose their balance stepping down to the street from a raised sidewalk, children on scooters, toddlers who just have really short legs 🙂 All of these humans benefit from the curb cut even though the sidewalk is made this way to specifically ensure people using wheelchairs can manage the urban landscape safely. Designing your online classroom to meet the learning needs you know about — and the ones you don’t — is good, inclusive planning.

Using the Principles of UDL to Design Online Courses : Practical Tips

How to Provide Multiple Means for Engagement Online

Designing inclusive online classrooms begins with a commitment to systems and structures that enable students to know what they are learning, and why they are learning it. When it comes to learning, humans need to know what the learning is for and why it is relevant to them. Anything you can do to activate the brain’s “why” networks will support learners.

- Draw students’ attention to the learning goals for a module. We model this in the form of a list of learning objectives at the start of each module in this course. In many LMSs, instructors can create to-do lists for each module, and even link the to-do items to the course calendar. This gives learners an easy-to-see overview of what is expected and when the work is expected to be done. Importantly, use the same system for listing goals at the start of every module. Routines and consistency reduce the cognitive load for learners and enable them to quickly find what they need. You don’t want learners to have to waste time or energy trying to find out what they are supposed to be learning because this causes stress and may lead them to disengage before the learning even begins.

- Optimize relevance, value and authenticity. Use what you know about your learners and about their community to create content and activities that (a) connect to their interests and (b) that allow them to explore what they already know about a topic. You might use Flipgrid as a context for sharing personal connections to a particular idea; You might integrate a discussion forum for brainstorming; You might create a compelling prompt on VoiceThread to which students can respond using their voices; You might host small, synchronous group meetings through VideoConference to introduce the topic and generate some initial thinking about why this topic is important, meaningful and relevant to your learners. Some video conferencing tools (e.g., Zoom) allow the creation of Breakout Groups where a large group can be assigned to smaller conversation circles. Breakout groups can then return to a larger group session and share out one or two important ideas.

- Foster Collaboration and Community. Collaboration and community help build relationships. These relationships, in turn, help students to feel that their learning in your course is relevant and meaningful. In addition to the strategies suggested in Module 1, you might also consider bringing local community voices and resources into your online course. We often invite experts to talk to students in our bricks-and-mortar classrooms. Why not invite local community members with expertise to share into a video chat, or to record a conversation that can be posted and viewed asynchronously by learners? Depending on the age of your learners, you might also use social media platforms such as Twitter or chat apps such as Slack to create channels for the sharing of resources.

- Facilitate personal coping skills and be sure to affirm students’ progress. One-on-one conversations through email, on the telephone, or through video-chat can go a long way to helping students manage their work and feel like they are on the right track. Plan to design for periodic check-ins with your students and let students know how to get in touch with you if they have a question or a problem. You can also affirm students’ work by highlighting the great learning you have observed in their work. In my own online teaching practice, I send out a weekly message to all students in which I summarize all expectations for the week, but also affirm the great thinking that happened in alignment with course expectations the previous week. I try to design those messages so that by the end of the course, every student is mentioned at least once for having done something especially well, raised an important question or made an important connection.

- Model (and expect the use of ) language and behaviours that affirm our shared humanity, and demonstrate respect for diverse lived experiences, identities, and sexual orientations. In the design of your online courses, it is important to remember that we all live in human bodies. All of our bodies have strengths. All of our bodies have limitations. But it is always through these human bodies that we learn (Glenberg, 2010). Even though we are all humans living in human bodies, some human bodies are treated, by majority culture, and by our institutions and systems, as threats or problems. Some human bodies are policed differently than other bodies; some human bodies are viewed — especially in schools — through deficit orientations (e.g., Castagno & Brayboy, 2009; Paris, 2012). Accessible classrooms, however, are safe and welcoming for all human bodies.

Engagement and motivation depend, in part, on how safe a learner feels. If we want our students to “put themselves out there” or take risks in their learning, they have to know that their vulnerability will be respected, honoured and supported. For our students living in non-white, non cis-gendered bodies, or in bodies that look different in some way from typically developing human bodies — it is important to remember that these children and teens may not enjoy the privilege of feeling safe in the world. As teachers, in our careers, we will definitely teach people who are….transgender or who have non-binary gendered identities (for PJ candidates, remember that even little ones in elementary school may know that who they are on the inside and what their bodies look like to other people don’t seem to match up), people who are Lesbian, Gay, or Bisexual, people who are brown, black, Indigenous or otherwise identify as a person of colour (sometimes referred to summarily as BIPOC), people with physical disabilities, and people with cognitive and developmental differences. We will also teach students who belong to faith communities that have been subjected to hate-driven acts (and policies) of violence, students who are in the midst of linguistic and cultural transition due to immigration, and students who are neurodiverse in ways that we know about, and in ways that we don’t.

The good news is that because online courses are developed with intention and created so that students can access information asynchronously (i.e., at a time and from a place that works for them), teachers can use several methods to design safe spaces for learners who, because of their bodies, or because they may be perceived as “non dominant” in some way, have experienced systemic marginalization. To create safer spaces for your learners, you can…- Use images in your online course that provide diverse visual representations of human bodies. For royalty free imagery that you can use without worry of copyright infringement, use Image Search at Creative Commons.org or set the usage rights to “free to use or share” in the Google Image Search—Settings–Advanced Options.

- When you introduce yourself to students, use your pronouns (he/she/they) and invite others to share their pronouns in their introductory discussion forum posts or in their videos if they would like to.

- Create assignments that encourage learners to explore part of their lived experience in their own way, or that enable learners to speak back to dominant discourses about who they are. Consider video production assignments that allow children and teens to tell their own story, in their own words or that invite children to tell the story of an important place in their community in a way that is meaningful and authentic to them (e.g., Watt, 2019).

- In discussion forums, model the language you would like your learners to use. Show them how to describe, to explain, to critically evaluate, to analyze, to summarize — and, where appropriate, by using language that includes rather than excludes.

- In the texts, stories, and informational resources you provide, recommend or include, be intentional to include works produced by people with diverse identities and experiences. Include works written by LGBTQ2+ authors, that provide BIPOC perspectives, and that present non-dominant people as regular people living regular lives so that your students come to understand these lives and these bodies as part of the richness of the human tapestry rather than something to to be othered or different. For recommendations, KidLitCollective offers a fantastic list of books for school-aged children that are inclusive of multiple perspectives, and amplify the voices of authors with diverse identities https://wtpsite.com/

How to Provide Multiple Means of Representation Online

Providing multiple means of representation online includes helping your students to know how to adapt. Often, teachers need to show and help students practice the technical skills they need to be able to make use of digital learning environments. You can consult the full set of UDL recommendations for designing to support the “what” networks of learning. Here, however, we provide some important strategies and tips that all teachers can use in their online course designs.

- Design so that information can be customized, displayed and accessed through different modalities. UDLCenter offers a range of recommendations for the design of digital texts that can be modified by the reader to suit their needs in web browsers. For teachers, the following basic recommendations will help you to create accessible digital texts (which are in alignment with web content accessibility guidelines (WCAG) for the development of accessible web content):

- If you include an image (photo, diagram, graph) that contains important information, be sure that you also provide a description of the content in text so that people who may not be able to read the image can access the ideas.

- Check the contrast in your web-based materials. I recently learned about the importance of text-size and colour in determining how accessible information is online. If you’re not sure about whether your content is accessible or customizable, you can check it using tools such as Vischeck, which shows how text looks to someone who is colourblind, or WebAim that will check the font size and colour contrasts against web accessibility standards.

- Provide captioning for your pre-recorded video content. This can feel like a huge undertaking because often, you need to generate the transcript for the videos you produce. But, if you plan to include the transcript in your videos from the start, it’s not that difficult. Youtube does offer automatic, AI-generated captioning on videos that you post to your channel. You do, however, need to edit these for accuracy because machine learning is not as accurate as you are.

- Do include information that makes use of audio, video, images, colour, and/or graphics to convey information; just be sure that you describe the content in text so that screenreaders for the visually impaired can be used to access the information, and to caption videos. To create quick video presentations, you could use a tool like Animoto. To create multimodal infographics, you could use tools such as Piktochart or Canva. To create screencast videos where you narrate a demonstration for how to do something while capturing what you are doing on your screen, you could use a tool such as Screencast-o-Matic or Techsmith’s Capture (free) or one of their paid tools (SnagIt, or Camtasia).

- Encourage the use of translation tools so that English language learners in your classroom can access ideas as they build their English vocabulary. Provide easy-to-find links that your students can use to open these tools online. Google Translate is betting better all of the time. Linguee is another terrific resource that provides language learners with a range of examples of how words or phrases are used in both languages. The Linguee website also provides access to a tool called DeepL that allows for the translation of chunks of text.

- In the design of your materials, be sure to emphasize connections between ideas and to previous knowledges. Students need repeated, and multiple ways to connect to the most important new learnings, and to see patterns. When connections are made explicit for them, learning is generally supported. Show them, tell them, explain, describe, summarize, re-state — use multiple approaches over time to build schemas of understanding.

How to Provide Multiple Means of Action and Expression Online

Activating the “how” networks of learning is the third UDL dimension. Students benefit from choice and from variety when it comes to building new understandings and showing what they have learned. Plus, it is important for teachers to equip learners to use digital tools effectively. For younger learners who are just learning to type, for example, or who are just learning to navigate online environments, find information, create files and share them, teachers do need to provide a lot of “technical” support so that learners can show what they have learned, or are learning to do. Here are some tips for how you can support that learning and create opportunities for kids to show their learning using a range of tools and modalities.

- Some students will use assistive technologies to navigate your online course materials. UDL Center recommends that teachers design online content with “alternate keyboard commands”. Maybe you had no idea that there are a whole bunch of keyboard shortcuts for Windows, Macs and Chromebooks? As it turns out, there are! And these are important for many kids who may not be able to use a mouse to navigate. This chart might come in handy as you help your students learn how to do mange their technical environment.

- Provide and encourage kids to use digital tools that will help them show what they can do. Don’t shy away from encouraging students to use spellcheckers, or text-to-speech software because some teacher, somewhere said that these tools make things “too easy” or might “undermine” learning in some way. This makes very little sense in an UDL classroom. Your job is to match kids with tools that enable them to thrive. So…as recommended by the good folks at UDL Center (http://udlguidelines.cast.org/action-expression/expression-communication/construction-composition):

- Provide spellcheckers, grammar checkers, word prediction software. Google Docs, for example, provide all of these supports; Using Microsoft tools, these functions can also be enabled.

- Provide text-to-speech software (voice recognition), human dictation, recording. Google Read & Write is a Chrome extension, often available to students in Ontario through provincial licenses.

- Provide calculators, graphing calculators, geometric sketchpads, or pre-formatted graph paper. Try Geogebra or Geometer’s Sketchpad.

- For composition activities, or to help students understand the ways that arguments, and narrative structures are organized, use tools that help them keep their ideas organized. The folks at Reading Rockets and at CommonSense Media offer a range of applications that can be used to support writing and composition.

- Use story webs, story maps, outlining tools, or concept mapping tools. Online, try tools such as Popplet, and Canva for making or integrating graphic organizers in your online course materials.

- Provide Computer-Aided-Design (CAD), music notation (writing) software, or mathematical notation software. Suggestions: Use Thing

- Provide virtual or concrete mathematics manipulatives (e.g., base-10 blocks, algebra blocks)

- Use web applications (e.g., wikis, animation, presentation).

- Encourage students to make interactive, multimodal products that show their understandings. Apps to try? Powtoon. Thinglink. This Thinkglink, created by PhD Candidate Grace Ko at the University of Texas shows teachers the design of a physical classroom space that supports learners with special learning needs — maybe this one will inspire you as well!

2.2 Reflect

Having reviewed these recommendations for the design of online learning environments that prioritize equity and accessibility, reflect on the most significant change that you now realize you will need to make to your online teaching this year. What single thing do you now realize that you need to do differently?

2.3 Practice

Think of a student with whom you have worked with in your life, and who had a particular learning need of which you were aware. It could be anything at all — maybe the child needed additional supports so that she felt included, represented and heard. Maybe the child needed sensory accommodations, or needed to show their learning using voice, or imagery. Anything at all.

Now, take 15 minutes to draft up a plan for how you could use the UDL framework to design a single online learning lesson.

Ready to move on to Module 3?

Module 3 focuses on strategies for setting up an effective online course.

Module 2 References

Brown, J. S., Collins, A., & Duguid, P. (1989). Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educational Researcher, 18(1), 32–42.

Castagno, A. E., & Brayboy, B. M. J. (2009). Culturally responsive schooling for Indigenous youth: A review of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 78(4), 941–993. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654308323036

Glenberg, A. M. (2010). Embodiment as a unifying perspective for psychology. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science, 586–596. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcs.55

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2018. How People Learn II: Learners, Contexts, and Cultures. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/24783.

Paris, D. (2012). Culturally sustaining pedagogy. Educational Researcher, 41(3), 93–97. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189×12441244

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

Watt, D. (2019). Video production in elementary teacher education as a critical digital literacy practice. Media and Communication, 7(2 Critical Perspectives), 82–99. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v7i2.1967